Classification of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The classification of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas is based upon cultural regions, geography, and linguistics. Anthropologists have named various cultural regions, with fluid boundaries, that are generally agreed upon with some variation. These cultural regions are broadly based upon the locations of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas from early European and African contact beginning in the late 15th century. When Indigenous peoples have been forcibly removed by nation-states, they retain their original geographic classification. Some groups span multiple cultural regions.

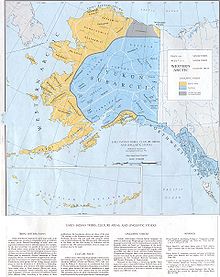

Canada, Greenland, United States, and northern Mexico

editIn the United States and Canada, ethnographers commonly classify Indigenous peoples into ten geographical regions with shared cultural traits, called cultural areas.[1] Greenland is part of the Arctic region. Some scholars combine the Plateau and Great Basin regions into the Intermontane West, some separate Prairie peoples from Great Plains peoples, while some separate Great Lakes tribes from the Northeastern Woodlands.

Arctic

edit

- Paleo-Eskimo, prehistoric cultures, Russia, Alaska, Canada, Greenland, 2500 BCE–1500 CE

- Arctic small tool tradition, prehistoric culture, 2500 BCE, Bering Strait

- Pre-Dorset, eastern Arctic, 2500–500 BCE

- Saqqaq culture, Greenland, 2500–800 BCE

- Independence I, northeastern Canada and Greenland, 2400–1800 BCE

- Independence II culture, northeastern Canada and Greenland, 800–1 BCE)

- Groswater, Labrador and Nunavik, Canada

- Dorset culture, 500 BCE–1500 CE, Alaska, Canada

- Aleut (Unangan), Aleutian Islands of Alaska, and Kamchatka Krai, Russia

- Inuit, Russia, Alaska, Canada, Greenland

- Thule, proto-Inuit, Alaska, Canada, Greenland, 900–1500 CE

- Birnirk culture, prehistoric Inuit culture, Alaska, 500 CE–900 CE

- Greenlandic Inuit, Greenland

- Kalaallit, west Greenland

- Avanersuarmiut (Inughuit), north Greenland

- Tunumiit, east Greenland

- Inuvialuit, western Canadian Arctic

- Iñupiat, north and northwest Alaska

- Thule, proto-Inuit, Alaska, Canada, Greenland, 900–1500 CE

- Yupik peoples (Yup'ik), Alaska and Russia

- Alutiiq (Sugpiaq, Pacific Yupik), Alaska Peninsula, coastal and island areas of south central Alaska

- Central Alaskan Yup'ik people, west central Alaska

- Cup'ik, Hooper Bay and Chevak, Alaska

- Nunivak Cup'ig people (Cup'ig), Nunivak Island, Alaska

- Siberian Yupik, Russian Far East and St. Lawrence Island, Alaska

Subarctic

edit- Ahtna (Ahtena, Nabesna)

- Anishinaabe – see also Northeastern Woodlands

- Atikamekw, Quebec

- Chipewyan, Alaskan interior, Western Canada

- Cree, Central and Eastern Canada, North Dakota

- Dakelh (Carrier), British Columbia

- Babine, British Columbia

- Wet'suwet'en, British Columbia

- Deg Hit’an (Deg Xinag, Degexit’an, Kaiyuhkhotana), Alaska[2]

- Dena’ina (Tanaina), Alaska

- Dane-zaa (Beaver, Dunneza), Alberta, British Columbia

- Gwich'in (Kutchin, Loucheaux), Alaska, Yukon

- Hän, Alaska, Yukon

- Holikachuk, Alaska

- Innu (Montagnais), Labrador, Quebec

- Kaska (Nahane)

- Kolchan (Upper Kuskokwim)

- Koyukon, Alaska

- Naskapi

- Sekani

- Sahtú (North Slavey, Bearlake, Hare, Mountain), Northwest Territories

- Slavey (Awokanak, Slave, Deh Gah Got'ine, Deh Cho), Alberta, British Columbia[3]

- Tagish

- Tahltan

- Lower Tanana

- Middle Tanana

- Upper Tanana

- Tanacross

- Tasttine (Beaver)

- Tli Cho

- Inland Tlingit

- Tsetsaut (extinct)

- Tsilhqot'in (Chilcotin)

- Northern Tutchone

- Southern Tutchone

- Yellowknives

Pacific Northwest coast

edit- Alsea, Oregon

- Heiltsuk

- Nuxalk

- Tsleil-Waututh First Nation

- Chehalis (Upper and Lower), Washington

- Chehalis (BC), Fraser Valley

- Chemakum, Washington (extinct)

- Chetco – see Tolowa

- Chinook Dialects: (Lower Chinook, Upper Chinook, Clackamas, Wasco)

- Clallam – see Klallam

- Clatsop

- Comox, Vancouver Island/BC Georgia Strait

- Coos, Hanis, Oregon

- Lower Coquille (Miluk), Oregon

- Upper Coquille

- Cowichan, Southern Vancouver Island and Georgia Strait

- Lower Cowlitz, Washington

- Duwamish, Washington

- Eyak, Alaska

- Galice

- Gitxsan, British Columbia

- Haida (Dialects: Kaigani, Skidegate, Masset), BC & Alaska

- Haisla BC North/Central Coast

- Heiltsuk BC Central Coast

- Hoh Washington

- Kalapuya (Calapooia, Calapuya, Tfalatim, Yamel, Yaquina, Yoncalla), Oregon

- Central Kalapuya, Oregon

- North Kalapuya, Oregon

- South Kalapuya (Yonkalla, Yoncalla), Oregon

- Klallam (Clallam, Dialects: Klallam (Lower Elwha), S'Klallam (Jamestown), S'Klallam (Port Gamble))

- Klickitat

- Kwalhioqua

- Kwakwaka'wakw, British Columbia

- Koskimo

- 'Namgis

- Laich-kwil-tach (Euclataws or Yuculta)

- Lummi, Washington

- Makah, Washington

- Muckleshoot, Washington

- Musqueam, BC Lower Mainland (Vancouver)

- Nisga'a, British Columbia

- Nisqually, Washington

- Nooksack, Washington

- Nuu-chah-nulth West Coast of Vancouver Island

- Nuxalk (Bella Coola) – BC Central Coast

- Oowekeno – see Wuikinuxv

- Pentlatch, Vancouver Island and Georgia Strait

- Puyallup, Washington

- Quileute, Washington

- Quinault, Washington

- Rivers Inlet – see Wuikinuxv

- Rogue River or Upper Illinois (Chasta Costa), Oregon, California

- Saanich Southern Vancouver Island/Georgia Strait

- Samish, Washington

- Sauk-Suiattle, Washington

- Sechelt, BC Sunshine Coast/Georgia Strait (Shishalh)

- Shoalwater Bay Tribe, Washington

- Siletz, Oregon

- Siuslaw, Oregon

- Skagit

- Skokomish, Washington

- Sliammon, BC Sunshine Coast/Georgia Strait (Mainland Comox)

- Snohomish

- Snoqualmie

- Snuneymuxw (Nanaimo), Vancouver Island

- Songhees (Songish), Southern Vancouver Island/Strait of Juan de Fuca

- Sooke, Southern Vancouver Island/Strait of Juan de Fuca

- Squamish (Skwxwu7mesh), British Columbia

- Squaxin Island Tribe Washington

- Spokane Washington

- Stillaguamish Washington

- Sto:lo, BC Lower Mainland/Fraser Valley

- Steilacoom, Coast Salish, Puget Sound, Washington (extinct)[4]

- Suquamish, Washington

- Swinomish, Washington

- Tait

- Takelma Oregon

- Talio

- Tillamook (Nehalem) Oregon

- Tlatlasikoala

- Tlingit, Alaska

- Tolowa-Tututni, Northern California

- Tsimshian

- Tsleil-waututh (Burrard), British Columbia

- Tulalip, Washington

- Twana, Washington

- Tzouk-e (Sooke), Vancouver Island

- Lower Umpqua, Oregon

- Upper Umpqua, Oregon

- Upper Skagit Washington

- Wuikinuxv (Owekeeno), BC Central Coast

Northwest Plateau

editChinook peoples

edit- Clackamas, OR

- Clatsop, OR

- Kathlamet (Cathlamet), Washington

- Multnomah

- Wasco-Wishram, OR and WA

- Watlata, WA

Interior Salish

edit- Chelan

- Coeur d'Alene Tribe, ID, MT, WA

- Entiat, WA

- Flathead (Selisch or Salish), ID, MT

- Kalispel (Pend d'Oreilles), MT, WA

- Lower Kalispel, WA

- Upper Kalispel, MT

- In-SHUCK-ch, BC (Lower Lillooet)

- Lil'wat, BC (Lower Lillooet)

- Methow, WA

- Nespelem, WA

- Nlaka'pamux (Thompson people), BC

- Nicola people (Thompson-Okanagan confederacy)

- Sanpoil, WA

- Secwepemc, BC (Shuswap people)

- Sinixt (Lakes), BC, ID, and WA

- Sinkayuse (Sinkiuse-Columbia), WA (extinct)

- Spokane people, WA

- Syilx (Okanagan), BC, WA

- St'at'imc, BC (Upper Lillooet)

- Wenatchi (Wenatchee), WA

Sahaptin people

edit- Cowlitz, (Upper Cowlitz, Taidnapam), Washington

- Klickitat, Washington

- Nez Perce, Idaho

- Tenino (Tygh, Warm Springs), Oregon

- Umatilla, Idaho, Oregon

- Walla Walla, WA

- Wanapum, WA

- Wauyukma

- Wyam (Lower Deschutes)

- Yakama, WA

Other or both

edit- Cayuse, Oregon, Washington

- Celilo (Wayampam), Oregon

- Cowlitz, Washington

- Kalapuya, northwest Oregon

- Atfalati (Tualatin, northwest OregonR

- Mohawk River, northwest Oregon

- Santiam, northwest Oregon

- Yaquina, northwest Oregon

- Klamath, Oregon

- Kutenai (Kootenai, Ktunaxa), British Columbia, ID, and MT

- Lower Snake people: Chamnapam, Wauyukma, Naxiyampam

- Modoc, formerly California, now Oklahoma and Oregon

- Molala (Molale), Oregon

- Nicola Athapaskans (extinct), British Columbia

- Palus (Palouse), Idaho, Oregon, and Washington

- Upper Nisqually (Mishalpan), Washington

Great Plains

editIndigenous peoples of the Great Plains are often separated into Northern and Southern Plains tribes.

- Anishinaabeg (Anishinape, Anicinape, Neshnabé, Nishnaabe) (see also Subarctic, Northeastern Woodlands)

- Saulteaux (Nakawē), Manitoba, Minnesota and Ontario; later Alberta, British Columbia, Montana, Saskatchewan

- Odawa people (Ottawa), Ontario,[5] Michigan, later Oklahoma

- Potawatomi, Michigan,[5] Ontario, Indiana, Wisconsin, later Oklahoma

- Apache (see also Southwest)

- Lipan Apache, New Mexico, Texas

- Plains Apache (Kiowa Apache), Oklahoma

- Querecho Apache, Texas

- Arapaho (Arapahoe), formerly Colorado, currently Oklahoma and Wyoming

- Arikara (Arikaree, Arikari, Ree), North Dakota

- Atsina (Gros Ventre), Montana

- Blackfoot

- Kainai Nation (Káínaa, Blood), Alberta

- Northern Peigan (Aapátohsipikáni), Alberta

- Blackfeet, Southern Piegan (Aamsskáápipikani), Montana

- Siksika (Siksikáwa), Alberta

- Cheyenne, Montana, Oklahoma

- Suhtai, Montana, Oklahoma

- Comanche, Oklahoma, Texas

- Plains Cree, Montana

- Crow (Absaroka, Apsáalooke), Montana

- Escanjaques, Oklahoma

- Hidatsa, North Dakota

- Iowa (Ioway), Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma

- Kaw (Kansa, Kanza), Oklahoma

- Kiowa, Oklahoma

- Mandan, North Dakota

- Métis people (Canada), North Dakota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta

- Missouri (Missouria), Oklahoma

- Omaha, Nebraska

- Osage, Oklahoma, formerly Arkansas, Missouri

- Otoe (Oto), Oklahoma

- Pawnee, Oklahoma

- Chaui, Oklahoma[6]

- Kitkehakhi, Oklahoma[6]

- Pitahawirata, Oklahoma[6]

- Skidi, Oklahoma[6]

- Ponca, Nebraska, Oklahoma

- Quapaw, formerly Arkansas, Oklahoma

- Sioux

- Dakota, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Manitoba, Saskatchewan

- Lakota (Teton), Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Saskatchewan

- Nakoda (Stoney), Alberta

- Nakota, Assiniboine (Assiniboin), Montana, Saskatchewan

- Teyas, Texas

- Tonkawa, Oklahoma

- Tsuu T’ina, (Sarcee, Sarsi, Tsuut’ina), Alberta

- Wichita and Affiliated Tribes (Kitikiti'sh), Oklahoma, formerly Texas and Kansas

Eastern Woodlands

editNortheastern Woodlands

edit- Abenaki (Tarrantine), Quebec, Maine, New Brunswick, New Hampshire, and Vermont

- Eastern Abenaki, Quebec, Maine, and New Hampshire[5]

- Western Abenaki: Quebec, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont[5]

- Annamessex, Annemessex, formerly Eastern Shore of Maryland

- Anishinaabeg (Anishinape, Anicinape, Neshnabé, Nishnaabe) (see also Subarctic, Plains)

- Algonquin,[7] Quebec, Ontario

- Nipissing,[7] Ontario[5]

- Ojibwe (Chippewa, Ojibwa, Ojibway), Ontario, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin,[5] and North Dakota

- Mississaugas, Ontario

- Saulteaux (Nakawē), Ontario

- Odawa people (Ottawa), Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Ontario;[5] later Oklahoma

- Potawatomi, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan,[5] Ontario, Wisconsin; later Kansas and Oklahoma

- Accomac people, formerly Eastern Shore of Virginia

- Accohannock, formerly Eastern Shore of Virginia

- Gingaskin, formerly Eastern Shore of Virginia

- Adena culture (1000–200 BCE) formerly Ohio, Indiana, West Virginia, Kentucky, New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland

- Assateague, formerly Maryland[8]

- Attawandaron (Neutral Confederacy), formerly Ontario[5]

- Beothuk, formerly Newfoundland[5]

- Chowanoc, Chowanoke, formerly North Carolina

- Choptank people, formerly Maryland[8]

- Conoy, Virginia,[8] Maryland

- Fort Ancient culture (1000–1750 CE), formerly Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, and West Virginia

- Erie, formerly Pennsylvania, New York[5]

- Etchemin, formerly Maine

- Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), southern Wisconsin and Nebraska, formerly northern Illinois,[5] Iowa, and Nebraska

- Honniasont, formerly Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia

- Hopewell tradition, formerly Ohio, Illinois, and Kentucky, and Black River region, 200 BCE–500 CE

- Housatonic, formerly Massachusetts and New York[9]

- Illinois Confederacy (Illiniwek), formerly Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri[5]

- Iroquois Confederacy[7] (Haudenosaunee), currently Ontario, Quebec, and New York[5]

- Cayuga, currently New York,[5]Ontario, and Oklahoma

- Mohawk, New York,[5]Ontario, and Quebec

- Oneida, New York,[5]Ontario, and Wisconsin

- Onondaga, New York,[5]Ontario

- Seneca, New York,[5]Ontario, and Oklahoma

- Mingo, formerly Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia

- Tuscarora, formerly North Carolina, currently New York and Ontario

- Kickapoo, formerly Michigan,[5] Illinois, and Missouri; currently Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Mexico

- Laurentian (St. Lawrence Iroquoians), formerly New York, Ontario, and Quebec, ca. 1300–1580 CE

- Lenni Lenape (Delaware), formerly Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey; currently Ontario, Wisconsin and Oklahoma

- Munsee-speaking subgroups, formerly Long Island and southeastern New York;[10] currently Wisconsin

- Canarsie (Canarsee), formerly Long Island New York[11]

- Esopus, formerly New York,[10] later Ontario and Wisconsin

- Hackensack, formerly New York[10]

- Haverstraw (Rumachenanck), New York[12]

- Kitchawank (Kichtawanks, Kichtawank), New York[12]

- Minisink, formerly New York[10]

- Navasink,[12] formerly north shore of New Jersey

- Sanhican (Raritan), formerly Monmouth County, New Jersey

- Sinsink (Sintsink), formerly Westchester County, New York[12]

- Siwanoy, formerly New York and Connecticut

- Tappan, formerly New York[13]

- Waoranecks[14]

- Wappinger (Wecquaesgeek, Nochpeem), formerly New York[9][15]

- Warranawankongs[14]

- Wiechquaeskeck, formerly New York[10]

- Wisquaskeck (Raritan), formerly Westchester County, New York[12]

- Unami-speaking subgroups

- Acquackanonk, formerly Passaic River in northern New Jersey

- Okehocking, formerly southeast Pennsylvania[14]

- Unalachtigo, formerly Delaware, New Jersey

- Munsee-speaking subgroups, formerly Long Island and southeastern New York;[10] currently Wisconsin

- Mahican (Stockbridge Mahican)[7] formerly Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont[5][9]

- Manahoac, Virginia[16]

- Mascouten, formerly Michigan[5]

- Massachusett, formerly Massachusetts[7][17]

- Ponkapoag, formerly Massachusetts

- Meherrin, Virginia,[18] North Carolina

- Menominee, Wisconsin[5]

- Meskwaki (Fox), formerly Michigan,[5] currently Iowa

- Mi'kmaq (Micmac), New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Quebec,[5] and Maine

- Mohegan,[7] Connecticut

- Monacan, Virginia[19]

- Montaukett (Montauk),[7] New York

- Monyton (Monetons, Monekot, Moheton) (Siouan), West Virginia and Virginia

- Nansemond, Virginia

- Nanticoke, Delaware and Maryland[5]

- Narragansett, Rhode Island[7]

- Niantic, coastal Connecticut[7][17]

- Nipmuc (Nipmuck), Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island[17]

- Nottaway, Virginia[18]

- Occaneechi (Occaneechee), Virginia,[18][20][21]

- Passamaquoddy, New Brunswick, and Maine[5]

- Patuxent, Maryland[8]

- Paugussett, Connecticut[7]

- Peoria, Illinois, currently Oklahoma

- Mitchigamea, formerly Illinois, currently Oklahoma

- Moingona, formerly Illinois, currently Oklahoma

- Tamaroa, formerly Illinois, currently Oklahoma

- Wea, formerly Indiana, currently Oklahoma

- Pennacook tribe, formerly Massachusetts, New Hampshire[22]

- Penobscot, Maine

- Pequot, Connecticut[7]

- Petun (Tionontate), Ontario[5]

- Piscataway, Maryland[8]

- Pocumtuc, western Massachusetts[17]

- Podunk, formerly New York,[17] eastern Hartford County, Connecticut

- Powhatan Confederacy, Virginia[8]

- Appomattoc, Virginia

- Arrohateck, Virginia

- Chesapeake, Virginia

- Chesepian, Virginia

- Chickahominy, Virginia[18]

- Kiskiack, Virginia

- Mattaponi, Virginia

- Nansemond, Virginia[18]

- Paspahegh, Virginia

- Potomac (Patawomeck), Virginia

- Powhatan, Virginia

- Pamunkey, Virginia[18]

- Quinnipiac, Connecticut,[7] eastern New York, northern New Jersey

- Rappahannock, Virginia

- Saponi, North Carolina, Virginia,[18] later Pennsylvania, New York, and Ontario[21]

- Sauk (Sac), formerly Michigan,[5] currently Iowa, Oklahoma

- Schaghticoke, western Connecticut[7]

- Shawnee, formerly Ohio,[5] Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, currently Oklahoma

- Shinnecock,[7] Long Island, New York[17]

- Stegarake, formerly Virginia[16]

- Stuckanox (Stukanox), Virginia[18]

- Conestoga (Susquehannock), Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, West Virginia[5]

- Tauxenent (Doeg), Virginia[23]

- Tunxis (Massaco), Connecticut[7]

- Tuscarora, formerly North Carolina, Virginia, currently New York

- Tutelo (Nahyssan), Virginia,[18][20] later Pennsylvania, New York, and Ontario[21]

- Unquachog (Poospatuck), Long Island, New York[17]

- Wabanaki, Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Quebec[7]

- Wampanoag, Massachusetts[7]

- Wangunk (Mattabeset), formerly Connecticut[7]

- Wawyachtonoc, formerly Connecticut, New York[9]

- Weapemeoc, formerly northern North Carolina

- Wenro, formerly New York[5][7]

- Wicocomico, formerly Maryland, Virginia

- Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Quebec[5]

- Wyandot (Huron), Ontario south of Georgian Bay, later Kansas and Michigan, and currently Oklahoma and Wendake, Quebec

Southeastern Woodlands

editMost of these no longer exist as tribes.

- Acolapissa (Colapissa), Louisiana and Mississippi[24]

- Ais, eastern coastal Florida[25]

- Alafay (Alafia, Pojoy, Pohoy, Costas Alafeyes, Alafaya Costas), Florida[26]

- Amacano, Florida west coast[27]

- Apalachee, northwestern Florida[28]

- Atakapa (Attacapa), Louisiana west coast and Texas southwestern coast[28]

- Avoyel ("little Natchez"), Louisiana[19][24]

- Bayogoula, southeastern Louisiana[19][24]

- Biloxi, formerly Mississippi,[24][28] currently Louisiana

- Caddo Confederacy, formerly Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas,[28][30] currently Oklahoma

- Adai (Adaizan, Adaizi, Adaise, Adahi, Adaes, Adees, Atayos), Louisiana and Texas[24]

- Cahinnio, southern Arkansas[30]

- Doustioni, north central Louisiana[30]

- Eyeish (Hais), eastern Texas[30]

- Hainai, eastern Texas[30]

- Hasinai, eastern Texas[30]

- Kadohadacho, northeastern Texas, southwestern Arkansas, northwestern Louisiana[30]

- Nabedache, eastern Texas[30]

- Nabiti, eastern Texas[30]

- Nacogdoche, eastern Texas[30]

- Nacono, eastern Texas[30]

- Nadaco, eastern Texas[30]

- Nanatsoho, northeastern Texas[30]

- Nasoni, eastern Texas[30]

- Natchitoches, Lower: central Louisiana, Upper: northeastern Texas[30]

- Neche, eastern Texas[30]

- Nechaui, eastern Texas[30]

- Ouachita, northern Louisiana[30]

- Tula, western Arkansas[30]

- Yatasi, northwestern Louisiana[30]

- Calusa, southwestern Florida[26][28]

- Cape Fear Indians, North Carolina southern coast[24]

- Capinan (Capina, Moctobi), Mississippi

- Catawba (Esaw, Usheree, Ushery, Yssa),[31] North Carolina, currently South Carolina[28]

- Chacato (Chatot, Chactoo), Florida panhandle, later southern Alabama and Mississippi, then Louisiana[24]

- Chakchiuma, Alabama and Mississippi,[28] merged into Chickasaw, currently Oklahoma

- Chawasha (Washa), Louisiana[24]

- Cheraw (Chara, Charàh), North Carolina

- Cherokee, western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, later Georgia, northwestern South Carolina, northern Alabama, Arkansas, Texas, Mexico, and currently North Carolina and Oklahoma[32]

- Chickanee (Chiquini), North Carolina

- Chickasaw, Alabama and Mississippi,[28] currently Oklahoma[32]

- Chicora, coastal South Carolina[19]

- Chine, Florida

- Chisca (Cisca), southwestern Virginia[19] later in Florida[33]

- Chitimacha, currently Louisiana[28]

- Choctaw, formerly Alabama; currently Mississippi,[28] Louisiana, and Oklahoma[32]

- Chowanoc (Chowanoke), North Carolina

- Congaree (Canggaree), South Carolina[24][34]

- Coree, North Carolina[19]

- Croatan, North Carolina

- Cusabo, coastal South Carolina[28]

- Eno, North Carolina[24]

- Grigra (Gris), Mississippi[35]

- Guacata (Santalûces), eastern coastal Florida[26]

- Guacozo, Florida

- Guale (Cusabo, Iguaja, Ybaja), coastal Georgia[24][28]

- Guazoco, southwestern Florida coast[26]

- Houma, Louisiana and Mississippi[28]

- Jaega (Jobe), eastern coastal Florida[25]

- Jaupin (Weapemoc), North Carolina

- Jororo, Florida interior[26]

- Keyauwee, North Carolina[24]

- Koasati (Coushatta), formerly eastern Tennessee,[28] currently Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas

- Koroa, Mississippi[24]

- Luca, southwestern Florida coast[26]

- Lumbee, currently North Carolina

- Machapunga, North Carolina

- Matecumbe (Matacumbêses, Matacumbe, Matacombe), Florida Keys[26]

- Mayaca, Florida[26]

- Mayaimi (Mayami), interior Florida[25]

- Mayajuaca, Florida

- Mikasuki (Miccosukee), currently Florida

- Mobila (Mobile, Movila), northwestern Florida and southern Alabama[28]

- Mocoso, western Florida[25][26]

- Mougoulacha, Mississippi[19]

- Muscogee (Creek), Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida; currently Oklahoma and Alabama

- Abihka, Alabama,[29] currently Oklahoma

- Alabama, formerly Alabama,[29] southwestern Tennessee, and northwestern Mississippi,[24][28] currently Oklahoma and Texas

- Apalachicola Province, (Lower Towns of the Muscogee (Creek) Confederacy), Alabama and Georgia[36]

- Chiaha, Creek Confederacy, Alabama[29]

- Eufaula tribe, Georgia, currently Oklahoma

- Kialegee Tribal Town, Alabama, currently Oklahoma

- Osochee (Osochi, Oswichee, Usachi, Oosécha), Creek Confederacy, Alabama[24][29]

- Talapoosa, Creek Confederacy, Alabama[29]

- Thlopthlocco Tribal Town, Alabama, Georgia, currently Oklahoma

- Tukabatchee, Muscogee Creek Confederacy, Alabama[29]

- Naniaba, northwestern Florida and southern Alabama[28]

- Natchez, Louisiana and Mississippi[28] currently Oklahoma

- Neusiok (Newasiwac, Neuse River Indians), North Carolina[24]

- Norwood culture, Apalachee region, Florida, c. 12,000–4500 BCE

- Mosopelea (Ofo), Arkansas and Mississippi,[28] eastern Tennessee,[24] currently Louisiana

- Okchai (Ogchay), central Alabama[24]

- Okelousa, Louisiana[24]

- Opelousas, Louisiana[24]

- Pacara, Florida

- Pamlico, North Carolina

- Pascagoula, Mississippi coast[19]

- Pee Dee (Pedee), South Carolina[24][37] and North Carolina

- Pensacola, Florida panhandle and southern Alabama[28]

- Potoskeet, North Carolina

- Quinipissa, southeastern Louisiana and Mississippi[29]

- Roanoke, North Carolina

- Saluda (Saludee, Saruti), South Carolina[24]

- Santee (Seretee, Sarati, Sati, Sattees), South Carolina (no relation to Santee Sioux), South Carolina[24]

- Santa Luces, Florida

- Saponi, North Carolina, Virginia,[18] later Pennsylvania, New York, and Ontario[21]

- Saura, North Carolina

- Saxapahaw (Sissipahaw, Sissipahua, Shacioes), North Carolina[24]

- Secotan, North Carolina

- Seminole, currently Florida and Oklahoma[32]

- Sewee (Suye, Joye, Xoye, Soya), South Carolina coast[24]

- Shakori, North Carolina

- Shoccoree (Haw), North Carolina,[24] possibly Virginia

- Sissipahaw, North Carolina

- Sugeree (Sagarees, Sugaws, Sugar, Succa), North Carolina and South Carolina[24]

- Surruque, east-central Florida[38]

- Suteree (Sitteree, Sutarees, Sataree), North Carolina

- Taensa, Mississippi[35]

- Taposa, Mississippi

- Tawasa, Alabama[39]

- Tequesta, southeastern coastal Florida[24][26]

- Timucua, Florida and Georgia[24][26][28]

- Acuera, central Florida[40]

- Agua Fresca (or Agua Dulce or Freshwater), interior northeast Florida[40]

- Arapaha, north-central Florida and south-central Georgia?[40]

- Cascangue, coastal southeast Georgia[40]

- Icafui (Icafi), coastal southeast Georgia[40]

- Mocama (Tacatacuru), coastal northeast Florida and coastal southeast Georgia[40]

- Northern Utina north-central Florida[40]

- Ocale, central Florida[40]

- Oconi, interior southeast Georgia[40]

- Potano, north-central Florida[40]

- Saturiwa, northeast Florida[40]

- Tacatacuru, coastal southeast Georgia[41]

- Tucururu (or Tucuru), Florida[40]

- Utina (or Eastern Utina), northeast-central Florida[42]

- Yufera, coastal southeast Georgia[40]

- Yui (Ibi), coastal southeast Georgia[40]

- Yustaga, north-central Florida[40]

- Taposa, Mississippi

- Tiou (Tioux), Mississippi[34]

- Tocaste, Florida[26]

- Tocobaga, Florida[24][26]

- Tohomé, northwestern Florida and southern Alabama[28]

- Tomahitan, eastern Tennessee

- Topachula, Florida

- Tunica, Arkansas and Mississippi,[28] currently Louisiana

- Utiza, Florida[25]

- Uzita, Tampa Bay, Florida[43]

- Vicela, Florida[25]

- Viscaynos, Florida

- Waccamaw, North Carolina, South Carolina

- Wateree (Guatari, Watterees), North Carolina[24]

- Waxhaw (Waxsaws, Wisack, Wisacky, Weesock, Flathead), North Carolina and South Carolina[24][37]

- Westo, Virginia and South Carolina,[19] extinct

- Winyaw, South Carolina coast[24]

- Woccon, North Carolina[24][37]

- Yamasee, Florida, Georgia[19]

- Yazoo, southeastern tip of Arkansas, eastern Louisiana, Mississippi[24][44]

- Yuchi (Euchee), central Tennessee,[24][28] later northwest Georgia, currently Oklahoma

Great Basin

edit- Ahwahnechee, Yosemite Valley, California

- Bannock, Idaho[45]

- Southern Paiute, Arizona, Nevada, Utah

- Chemehuevi, southeastern California

- Kaibab, northwestern Arizona[46]

- Kaiparowtis, southwestern Utah[46]

- Moapa, southern Nevada[46]

- Panaca[46]

- Panguitch, Utah[46]

- Paranigets, southern Nevada[46]

- Shivwits, southwestern Utah[46]

- Southern Paiute, Arizona, Nevada, Utah

- Coso People, of Coso Rock Art District in the Coso Range, Mojave Desert California

- Fremont culture (400 CE–1300 CE), formerly Utah[47]

- Kawaiisu, southern inland California[45]

- Mono, southeastern California

- Eastern Mono, southeastern California

- Western Mono or Owens Valley Paiute, eastern California and Nevada[45]

- Northern Paiute, eastern California, Nevada, Oregon, southwestern Idaho[45]

- Kucadikadi, Mono Lake Paiute, Mono Lake, California

- Guchundeka', Kuccuntikka, Buffalo Eaters[48][49]

- Tukkutikka, Tukudeka, Mountain Sheep Eaters, joined the Northern Shoshone[49]

- Boho'inee', Pohoini, Pohogwe, Sage Grass people, Sagebrush Butte People[48][49][50]

- Northern Shoshone, Idaho[45]

- Agaideka, Salmon Eaters, Lemhi, Snake River and Lemhi River Valley[50][51]

- Doyahinee', Mountain people[48]

- Kammedeka, Kammitikka, Jack Rabbit Eaters, Snake River, Great Salt Lake[50]

- Hukundüka, Porcupine Grass Seed Eaters, Wild Wheat Eaters, possibly synonymous with Kammitikka[50][52]

- Tukudeka, Dukundeka', Sheep Eaters (Mountain Sheep Eaters), Sawtooth Range, Idaho[50][51]

- Yahandeka, Yakandika, Groundhog Eaters, lower Boise, Payette, and Wiser Rivers[50][51]

- Kuyatikka, Kuyudikka, Bitterroot Eaters, Halleck, Mary's River, Clover Valley, Smith Creek Valley, Nevada[52]

- Mahaguadüka, Mentzelia Seed Eaters, Ruby Valley, Nevada[52]

- Painkwitikka, Penkwitikka, Fish Eaters, Cache Valley, Idaho and Utah[52]

- Pasiatikka, Redtop Grass Eaters, Deep Creek Gosiute, Deep Creek Valley, Antelope Valley[52]

- Tipatikka, Pinenut Eaters, northernmost band[52]

- Tsaiduka, Tule Eaters, Railroad Valley, Nevada[52]

- Tsogwiyuyugi, Elko, Nevada[52]

- Waitikka, Ricegrass Eaters, Ione Valley, Nevada[52]

- Watatikka, Ryegrass Seed Eaters, Ruby Valley, Nevada[52]

- Wiyimpihtikka, Buffalo Berry Eaters[52]

- Timbisha, aka Panamint or Koso, southeastern California

- Ute, Colorado, Utah, northern New Mexico[45]

- Capote, southeastern Colorado and New Mexico[53]

- Moanunts, Salina, Utah[54]

- Muache, south and central Colorado[53]

- Pahvant, western Utah[54]

- Sanpits, central Utah[54]

- Timpanogots, north central Utah[54]

- Uintah, Utah[53]

- Uncompahgre or Taviwach, central and northern Colorado[53]

- Weeminuche, western Colorado, eastern Utah, northwestern New Mexico[53]

- White River Utes (Parusanuch and Yampa), Colorado and eastern Utah[53]

- Washo, Nevada and California[55]

California

editNota bene: The California cultural area does not exactly conform to the state of California's boundaries, and many tribes on the eastern border with Nevada are classified as Great Basin tribes and some tribes on the Oregon border are classified as Plateau tribes.[56]

- Achomawi, Achumawi, Pit River tribe, northeastern California[57]

- Atsugewi, northeastern California[57]

- Cahuilla, southern California[57]

- Chumash, coastal southern California[57]

- Chilula, northwestern California[57]

- Chimariko, extinct, northwestern California[58]

- Cupeño, southern California[57]

- Eel River Athapaskan peoples

- Esselen, west-central California[57]

- Hupa, northwestern California[57]

- Juaneño, Acjachemem, southwestern California

- Karok, northwestern California[57]

- Kato, Cahto, northwestern California[57]

- Kitanemuk, south-central California[57]

- Konkow, northern-central California[57]

- Kumeyaay, Diegueño, Kumiai

- La Jolla complex, southern California, c. 6050–1000 BCE

- Luiseño, southwestern California[57]

- Maidu, northeastern California[57]

- Konkow, northern California

- Mechoopda, northern California

- Nisenan, Southern Maidu, northern California

- Miwok, Me-wuk, central California[57]

- Coast Miwok, west-central California[57]

- Lake Miwok, west-central California[57]

- Valley and Sierra Miwok

- Monache, Western Mono, central California[57]

- Nisenan, eastern-central California[57]

- Nomlaki, northwestern California[57]

- Ohlone, Costanoan, west-central California[57]

- Patwin, central California[57]

- Suisun, Southern Patwin, central California

- Pauma Complex, southern California, c. 6050–1000 BCE

- Pomo, northwestern and central-western California[57]

- Salinan, coastal central California[57]

- Serrano, southern California[57]

- Shasta northwestern California[57]

- Tataviam, Allilik (Fernandeño), southern California[57]

- Tolowa, northwestern California[57]

- Tongva, Gabrieleño, Fernandeño, San Clemente tribe, coastal southern California[57]

- Tubatulabal, south-central California[57]

- Wappo, north-central California[57]

- Whilkut, northwestern California[57]

- Wintu, northwestern California[57]

- Wiyot, northwestern California[57]

- Yana, northern-central California[57]

- Yokuts, central and southern California[57]

- Chukchansi, Foothill Yokuts, central California[57]

- Northern Valley Yokuts, central California[57]

- Tachi tribe, Southern Valley Yokuts, south-central California[57]

- Yuki, Ukomno'm, northwestern California[57]

- Yurok, northwestern California[57]

Southwest

editThis region is also called "Oasisamerica" and includes parts of what is now Arizona, Southern Colorado, New Mexico, Western Texas, Southern Utah, Chihuahua, and Sonora

- Southern Athabaskan

- Chiricahua Apache, New Mexico and Oklahoma

- Jicarilla Apache, New Mexico

- Lipan Apache, New Mexico, formerly Texas

- Mescalero Apache, New Mexico

- Navajo (Diné), Arizona and New Mexico

- San Carlos Apache, Arizona

- Tonto Apache, Arizona

- Western Apache (Coyotero Apache), Arizona

- White Mountain Apache, Arizona

- Comecrudo, Tamaulipas

- Cotoname (Carrizo de Camargo)

- Genízaro (detribalized Apache, Navajo, and Ute descendants), Arizona, New Mexico

- Halchidhoma, Arizona and California

- Hualapai, Arizona

- Havasupai, Arizona

- Hohokam, formerly Arizona

- Karankawa, formerly Texas

- Copano, formerly Texas

- La Junta, Texas, Chihuahua

- Mamulique, Texas, Nuevo León

- Manso, Texas, Chihuahua

- Mojave, Arizona, California, and Nevada

- O'odham, Arizona, Sonora

- Ak Chin, Arizona

- Akimel O'odham (formerly Pima), Arizona

- Tohono O'odham, Arizona and Mexico

- Qahatika, Arizona

- Hia C-eḍ Oʼodham, Arizona and Mexico

- Piipaash (Maricopa), Arizona

- Pima Bajo

- Pueblo peoples, Arizona, New Mexico, Western Texas

- Ancestral Pueblo, formerly Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah

- Hopi-Tewa (Arizona Tewa, Hano), Arizona, joined the Hopi during the Pueblo Revolt

- Hopi, Arizona

- Keres people, New Mexico

- Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico

- Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico

- Kewa Pueblo (formerly Santo Domingo Pueblo), New Mexico

- Laguna Pueblo, New Mexico

- San Felipe Pueblo, New Mexico

- Santa Ana Pueblo, New Mexico

- Zia Pueblo, New Mexico

- Tewa people, New Mexico

- Nambé Pueblo, New Mexico

- Ohkay Owingeh (formerly San Juan Pueblo), New Mexico

- Pojoaque Pueblo, New Mexico

- San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico

- Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico

- Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico

- Tiwa people, New Mexico

- Isleta Pueblo, New Mexico

- Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico

- Sandia Pueblo, New Mexico

- Taos Pueblo, New Mexico

- Ysleta del Sur Pueblo (Tigua Pueblo), Texas

- Piro Pueblo, New Mexico

- Tompiro, formerly New Mexico

- Towa people

- Jemez Pueblo (Walatowa), New Mexico

- Pecos (Ciquique) Pueblo, New Mexico

- Zuni people (Ashiwi), New Mexico

- Quechan (Yuma), Arizona and California

- Quems, formerly Coahuila and Texas

- Solano, Coahuila, Texas

- Tamique (Aranama), formerly Texas

- Toboso, Chihuahua and Coahuila

- Walapai, Arizona

- Yaqui (Yoreme), Arizona, Sonora

- Yavapai, Arizona

- Tolkapaya (Western Yavapai), Arizona

- Yavapé (Northwestern Yavapai), Arizona

- Kwevkapaya (Southeastern Yavapai), Arizona

- Wipukpa (Northeastern Yavapai), Arizona

Mexico and Mesoamerica

editThe regions of Oasisamerica, Aridoamerica, and Mesoamerica span multiple countries and overlap.

Aridoamerica

edit

- Acaxee

- Aranama (Hanáma, Hanáme, Chaimamé, Chariname, Xaraname, Taraname), southeast Texas

- Coahuiltecan, Texas, northern Mexico

- Chichimeca

- Cochimí, Baja California[63]

- Cocopa, Arizona, northern Mexico

- Garza, Texas, northern Mexico

- Guachimontone

- Guamare

- Guaycura, Baja California

- Guarijío, Huarijío, Chihuahua, Sonora[63]

- Huichol[63] (Wixáritari), Nayarit, Jalisco, Zacatecas, and Durango

- Kiliwa, Baja California

- Mayo,[63] Sonora and Sinaloa

- Monqui, Baja California

- Paipai, Akwa'ala, Kw'al, Baja California[64]

- Opata

- Otomi, central Mexico

- Patiri, southeastern Texas

- Pericúe, Baja California

- Pima Bajo[63]

- Seri[63]

- Tarahumara[63]

- Tepecano

- Tepehuán[63]

- Terocodame, Texas and Mexico

- Teuchitlan tradition

- Western Mexico shaft tomb tradition

- Yaqui,[63] Sonora and now southern Arizona

- Zacateco

Mesoamerica

edit

- Nahua, Guatemala and Mexico

- Cora people

- Huastec

- Huave (Wabi), Juchitán District, Oaxaca

- Lenca

- Maya, Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico

- Mazatec

- Mixtec

- Olmec

- Otomi

- Pipil

- Purépecha, also known as Tarascan

- Tlapanec

- Xinca

- Zapotec

- Toltec (900–1168 CE), Tula, Hildago

Circum-Caribbean

editPartially organized per Handbook of South American Indians.[65]

Caribbean

editAnthropologist Julian Steward defined the Antilles cultural area, which includes all of the Antilles and Bahamas, except for Trinidad and Tobago.[65]

- Arawak

- Caquetio, Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, and Venezuela

- Carib, Lesser Antilles

- Kalinago, Dominica

- Garifuna ("Black Carib"), Originally Dominica and Saint Vincent, currently Belize, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua

- Ciboney, Greater Antilles, c. 1000–300 BCE[66]

- Guanahatabey (Guanajatabey), Cuba, 1000 BCE

- Ciguayo, Hispaniola

- Ortoiroid, c. 5500–200 BCE[67]

- Coroso culture, Puerto Rico, 1000 BCE–200 CE[67]

- Krum Bay culture, Virgin Islands, St. Thomas, 1500–200 BCE[67]

- Saladoid culture, 500 BCE–545 CE[67]

Central America

editThe Central American culture area includes part of El Salvador, most of Honduras, all of Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, and some peoples on or near the Pacific coasts of Colombia and Ecuador.[65]

- Bagaces, Costa Rica

- Bokota, Panama

- Boruca, Costa Rica

- Bribri, Costa Rica

- Cabécar, Costa Rica

- Cacaopera (Matagalpa, Ulua), formerly El Salvador[68]

- Cayada, Ecuador

- Changuena, Panama

- Embera-Wounaan (Chocó, Wounaan), Colombia, Panama

- Choluteca, Honduras

- Coiba, Costa Rica

- Coito, Costa Rica

- Corobici, Costa Rica

- Desaguadero, Costa Rica

- Dorasque, Panama

- Guatuso, Costa Rica

- Guaymí, Panama

- Guetar, Costa Rica

- Kuna (Guna), Panama and Colombia

- Lenca, Honduras and El Salvador

- Mangue, Nicaragua

- Maribichocoa, Honduras and Nicaragua

- Miskito, Hondrus, Nicaragua

- Nagrandah, Nicaragua

- Ngöbe Buglé, Bocas del Toro, Panama

- Nicarao, Nicaragua

- Nicoya, Costa Rica

- Orotiña, Costa Rica

- Paparo, Panama

- Paya, Honduras

- Pech, northeastern Honduras

- Piria, Nicaragua

- Poton, Honduras and El Salvador

- Quepo, Costa Rica

- Rama, Nicaragua

- Sigua, Panama

- Subtiaba, Nicaragua

- Suerre, Costa Rica

- Sumo (Mayagna), Honduras and Nicaragua

- Terraba (Naso, Teribe, Tjër Di), Panama

- Tojar, Panama

- Tolupan (Jicaque), Honduras

- Ulva, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua

- Voto, Costa Rica

- Yasika, Nicaragua

Colombia and Venezuela

editThe Colombia and Venezuela culture area includes most of Colombia and Venezuela. Southern Colombia is in the Andean culture area, as are some peoples of central and northeastern Colombia, who are surrounded by peoples of the Colombia and Venezuela culture. Eastern Venezuela is in the Guianas culture area, and southeastern Colombia and southwestern Venezuela are in the Amazonia culture area.[65]

- Abibe, northwestern Colombia

- Aburrá, central Colombia

- Achagua (Axagua), eastern Colombia, western Venezuela

- Agual, western Colombia

- Amaní, central Colombia

- Ancerma, western Colombia

- Andaqui (Andaki), Huila Department, Colombia

- Andoque, Andoke, southeastern Colombia

- Antiochia, Colombia

- Arbi, western Colombia

- Arma, western Colombia

- Atunceta, western Colombia

- Auracana, northeastern Colombia

- Buriticá, western Colombia

- Caquetio, western Venezuela

- Calamari, northwestern Colombia

- Calima culture, western Colombia, 200 BCE–400 CE

- Caramanta, western Columbia

- Carate, northeastern Colombia

- Carare, northeastern Colombia

- Carex, northwestern Colombia

- Cari, western Colombia

- Carrapa, western Colombia

- Cartama, western Colombia

- Cauca, western Colombia

- Corbago, northeastern Colombia

- Cosina, northeastern Colombia

- Catio, northwestern Colombia

- Cenú, northwestern Colombia

- Cenufaná, northwestern Colombia

- Chanco, western Colombia

- Coanoa, northeastern Colombia

- Cuiba, east Colombia west Venezuela

- Cuica, western Venezuela

- Cumanagoto, eastern Venezuela

- Evéjito, western Colombia

- Fincenú, northwestern Colombia

- Gorrón, western Colombia

- Guahibo (Guajibo), eastern Colombia, southern Venezuela

- Guambía, western Colombia

- Guanes, Colombia, pre-Columbian culture

- Guanebucan, northeastern Colombia

- Guazuzú, northwestern Colombia

- Hiwi, western Colombia, eastern Venezuela

- Jamundí, western Colombia

- Kari'ña, eastern Venezuela

- Kogi, northern Colombia

- Lile, western Colombia

- Lache, central Colombia

- Mariche, central Venezuela

- Maco (Mako, Itoto, Wotuja, or Jojod), northeastern Colombia and western Venezuela

- Mompox, northwestern Colombia

- Motilone, northeastern Colombia and western Venezuela

- Naura, central Colombia

- Nauracota, central Colombia

- Noanamá (Waunana, Huaunana, Woun Meu), northwestern Colombia and Panama

- Nutabé, northwestern Colombia

- Opón, northeastern Colombia

- Pacabueye, northwestern Colombia

- Pancenú, northwestern Colombia

- Patángoro, central Colombia

- Paucura, western Colombia

- Pemed, northwestern Colombia

- Pequi people, western Colombia

- Picara, western Colombia

- Pozo, western Colombia

- Pumé (Yaruro), Venezuela

- Quimbaya, central Colombia, 4th–7th centuries CE

- Quinchia, western Colombia

- Sutagao, central Colombian

- Tahamí, northwestern Colombia

- Tairona, northern Colombia, pre-Columbian culture, 1st–11th centuries CE

- Tamalameque, northwestern Colombia

- Mariche, central Venezuela

- Timba, western Colombia

- Timote, western Venezuela

- Tinigua, Caquetá Department, Colombia

- Tolú, northwestern Colombia

- Toro, western Colombia

- Tupe, northeastern Colombia

- Turbaco people, northwestern Colombia

- Urabá, northwestern Colombia

- Urezo, northwestern Colombia

- U'wa, eastern Colombia, western Venezuela

- Waikerí, eastern Venezuela

- Wayuu (Wayu, Wayúu, Guajiro, Wahiro), northeastern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela

- Xiriguana, northeastern Colombia

- Yamicí, northwestern Colombia

- Yapel, northwestern Colombia

- Yarigui, northeastern Colombia

- Yukpa, Yuko, northeastern Colombia

- Zamyrua, northeastern Colombia

- Zendagua, northwestern Colombia

- Zenú, northwestern Colombia, pre-Columbian culture, 200 BCE–1600 CE

- Zopia, western Colombia

Guianas

edit

This region includes northern parts Colombia, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela, and parts of the Amazonas, Amapá, Pará, and Roraima States in Brazil.

- Acawai (6N 60W)

- Acokwa (3N 53W)

- Acuria (Akurio, Akuriyo), 5N 55W, Suriname

- Akawaio, Roraima, Brazil, Guyana, and Venezuela

- Amariba (2N 60W)

- Amicuana (2N 53W)

- Apalaí (Apalai), Amapá, Brazil

- Apirua (3N 53W)

- Apurui (3N 53W)

- Aracaret (4N 53W)

- Aramagoto (2N 54W)

- Aramisho (2N 54W)

- Arebato (7N 65W)

- Arekena (2N 67W)

- Arhuaco, northeastern Colombia

- Arigua

- Arinagoto (4N 63W)

- Arua (1N 50W)

- Aruacay, Venezuela

- Atorai (2N 59W)

- Atroahy (1S 62W)

- Auaké, Brazil and Guyana

- Baniwa (Baniva) (3N 68W), Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela

- Baraüana (1N 65W)

- Bonari (3S 58W)

- Baré (3N 67W)

- Caberre (4N 71 W)

- Cadupinago

- Cariaya (1S 63 W)

- Carib (Kalinago), Venezuela

- Carinepagoto, Trinidad

- Chaguan, Venezuela

- Chaima, Venezuela

- Cuaga, Venezuela

- Cuacua, Venezuela

- Cumanagoto, Venezuela

- Guayano, Venezuela

- Guinau (4N 65W)

- Hixkaryána, Amazonas, Brazil

- Hodï, Venezuela

- Inao (4N 65W)

- Ingarikó, Brazil, Guyana and Venezuela

- Jaoi (Yao), Guyana, Trinidad and Venezuela

- Kali'na, Brazil, Guyana, French Guiana, Suriname, Venezuela

- Lokono (Arawak, Locono), Guyana, Trinidad, Venezuela

- Macapa (2N 59W)

- Macushi, Brazil and Guyana

- Maipure (4N 67W)

- Maopityan (2N 59W)

- Mapoyo (Mapoye), Venezuela

- Marawan (3N 52W)

- Mariusa, Venezuela

- Marourioux (3N 53W)

- Nepuyo (Nepoye), Guyana, Trinidad and Venezuela

- Orealla, Guyana

- Palengue, Venezuela

- Palikur, Brazil, French Guiana

- Parauana (2N 63W)

- Parauien (3S 60W)

- Pareco, Venezuela

- Paria, Venezuela

- Patamona, Roraima, Brazil

- Pauishana (2N 62W)

- Pemon (Arecuna), Brazil, Guyana, and Venezuela

- Piapoco (3N 70W)

- Piaroa, Venezuela

- Pino (3N 54W)

- Piritú, Venezuela

- Purui (2N 52W)

- Saliba (Sáliva), Venezuela

- Sanumá, Venezuela, Brazil

- Shebayo, Trinidad

- Sikiana (Chikena, Xikiyana), Brazil, Suriname

- Tagare, Venezuela

- Tamanaco, Venezuela

- Tarumá (3S 60W)

- Tibitibi, Venezuela

- Tiriyó (Tarëno), Brazil, Suriname

- Tocoyen (3N 53W)

- Tumuza, Venezuela

- Wai-Wai, Amazonas, Brazil and Guyana

- Wapishana, Brazil and Guyana

- Warao (Warrau), Guyana and Venezuela

- Wayana (Oyana), Pará, Brazil

- Ya̧nomamö (Yanomami), Venezuela and Amazonas, Brazil

- Ye'kuana, Venezuela, Brazil

Eastern Brazil

editThis region includes parts of the Ceará, Goiás, Espírito Santo, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Pará, and Santa Catarina states of Brazil

- Apinajé (Apinaye Caroyo),[7] Rio Araguiaia

- Arara, Pará

- Atikum, Bahia and Pernambuco

- Bororo,[7] Mato Grosso

- Botocudo (Lakiãnõ)

- Carijo Guaraní[7]

- East Brazilian tradition, Precolumbian culture[7]

- Guató (Guato), Mato Grosso

- Kadiwéu (Guaicuru),[7] Mato Grosso do Sul

- Kaingang

- Karajá (Iny, Javaé),[7] Goiás, Mato Grosso, Pará, and Tocantins

- Kaxixó, Minas Gerais

- Kayapo (Cayapo, Mebêngôkre),[7] Mato Grosso and Pará

- Laklãnõ,[7] Santa Catarina

- Mehim (Krahô, Crahao),[7] Rio Tocantins

- Ofayé, Mato Grosso do Sul

- Parakatêjê (Gavião),[7] Pará

- Pataxó, Bahia

- Potiguara (Pitigoares),[7] Ceará

- Tabajara, Ceará

- Tapirapé (Tapirape)

- Terena, Mato Gross and Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil

- Tupiniquim, Espírito Santo

- Umutina (Barbados)[7]

- Xakriabá (Chakriaba, Chikriaba, or Shacriaba), Minas Gerais

- Xavánte (Shavante),[7] Mato Grosso

- Xerénte (Sherente),[7] Goiás

- Xucuru, Pernambuco

Andes

edit

- Andean Hunting-Collecting tradition, Argentina, 11,000–4,000 CE

- Awa-Kwaiker, northern Ecuador, southern Colombia

- Aymara, Bolivia,[69] Chile, Peru

- Callawalla (Callahuaya), Bolivia[69]

- Cañari, Ecuador

- Capulí culture, Ecuador, 800–1500 CE

- Cerro Narrio (Chaullabamba) (Precolumbian culture)

- Chachapoyas, Amazonas, Peru

- Chachilla (Cayapas)

- Chanka (Chanca), Peru

- Chavín, northern Peru, 900–200 BCE

- Chincha people, Peru (Precolumbian culture)

- Chipaya, Oruro Department, Bolivia[69]

- Chuquibamba culture (Precolumbian culture)

- Conchucos

- Diaguita

- Guangaia (Precolumbian culture)

- Ichuña microlithic tradition (Precolumbian culture)

- Inca Empire (Inka), based in Peru

- Jama-Coaque (Precolumbian culture)

- Killke culture, Peru, 900–1200 CE

- Kogi

- Kolla (Colla), Argentina, Bolivia, Chile

- La Tolita (Precolumbian culture)

- Las Vegas culture, coastal Ecuador, 8000 BCE–4600 BCE

- Lauricocha culture, Peru, 8000–2500 BCE

- Lima culture, Peru, 100–650 CE

- Maina, Ecuador, Peru

- Manteño-Huancavilca (Precolumbian culture)

- Milagro (Precolumbian culture)

- Mollo culture, Bolivia, 1000–1500 CE

- Muisca, Colombian highlands (Precolumbian culture)

- Pachacama (Precolumbian culture)

- Paez (Nasa culture), Colombian highlands (Precolumbian culture)

- Panzaleo (Precolumbian culture)

- Pasto

- Pijao, Colombia

- Quechua (Kichua, Kichwa), Bolivia[69]

- Quitu culture, 2000 BCE–1550 CE

- Salinar (Precolumbian culture)

- Saraguro

- Tiwanaku culture (Tiahuanaco), 400–1000 CE, Bolivia

- Tsáchila (Colorado), Ecuador

- Tuza-Piartal (Precolumbian culture)

- Uru, Bolivia,[69] Peru

- Uru-Murato, Bolivia

- Wari culture, central coast and highlands of Peru, 500–1000 CE

- Pocra culture, Ayacucho Province, Peru, 500–1000 CE

Pacific lowlands

edit- Amotape complex, northern coastal Peru, 9,000–7,100 BCE

- Atacameño (Atacama, Likan Antaí), Chile

- Awá, Colombia and Ecuador

- Bara, Colombia

- Cara culture, coastal Ecuador, 500 BCE–1550 CE

- Bahía, Ecuador, 500 BCE–500 CE

- Casma culture, coastal Peru, 1000–1400 CE

- Chancay, central coastal Peru, 1000–1450 CE

- Chango, coastal Peru, northern Chile

- Chimú, north coastal Peru, 1000–1450 CE

- Cupisnique (Precolumbian culture), 1000–200 BCE, coastal Peru

- Lambayeque (Sican culture), north coastal Peru, 750–1375 CE

- Machalilla culture, coastal Ecuador, 1500–1100 BCE

- Manteño civilization, western Ecuador, 850–1600 CE

- Moche (Mochica), north coastal Peru, 1–750 CE

- Nazca culture (Nasca), south coastal Peru, 1–700 CE

- Norte Chico civilization (Precolumbian culture), coastal Peru

- Paiján culture, northern coastal Peru, 8,700–5,900 BCE

- Paracas, south coastal Peru, 600–175 BCE

- Recuay culture, Peru (Precolumbian culture)

- Tallán (Precolumbian culture), north coastal Peru

- Valdivia culture, Ecuador, 3500–1800 BCE

- Virú culture, Piura Region, Peru, 200 BCE–300 CE

- Wari culture (Huari culture), Peru, 500–1000 CE

- Yukpa (Yuko), Colombia

- Yurutí, Colombia

Amazon

editNorthwestern Amazon

editThis region includes Amazonas in Brazil; the Amazonas and Putumayo Departments in Colombia; Cotopaxi, Los Rios, Morona-Santiago, Napo, and Pastaza Provinces and the Oriente Region in Ecuador; and the Loreto Region in Peru.

- Arabela, Loreto Region, Peru

- Arapaso (Arapaco), Amazonas, Brazil

- Baniwa

- Barbudo, Loreto Region, Peru

- Bora, Loreto Region, Peru

- Candoshi-Shapra (Chapras), Loreto Region, Peru

- Carútana (Arara), Amazonas, Brazil

- Chayahuita (Chaywita) Loreto Region, Peru

- Cocama, Loreto Region, Peru

- Cofán (Cofan), Putumayo Department, Colombia and Ecuador

- Cubeo (Kobeua), Amazonas, Brazil and Colombia

- Dâw, Rio Negro, Brazil

- Flecheiro

- Huaorani (Waorani, Waodani, Waos), Ecuador

- Hupda (Hup), Brazil, Colombia

- Jibito, Loreto Region, Peru

- Jivaroan peoples, Ecuador and Peru

- Kachá (Shimaco, Urarina), Loreto Region, Peru

- Kamsá (Sebondoy), Putumayo Department, Colombia

- Kanamarí, Amazonas, Brazil

- Kichua (Quichua)

- Cañari Kichua (Canari)

- Canelo Kichua (Canelos-Quichua), Pataza Province, Ecuador

- Chimborazo Kichua

- Cholos cuencanos

- Napo Runa (Napo Kichua, Quijos-Quichua, Napo-Quichua), Ecuador and Peru

- Saraguro

- Sarayacu Kichua, Pastaza Province, Ecuador

- Korubu, Amazonas, Brazil

- Kugapakori-Nahua

- Macaguaje (Majaguaje), Río Caquetá, Colombia

- Machiguenga, Peru

- Marubo

- Matsés (Mayoruna, Maxuruna), Brazil and Peru

- Mayoruna (Maxuruna)

- Miriti, Amazonas Department, Colombia

- Murato, Loreto Region, Peru

- Mura, Amazonas, Brazil

- Pirahã (Mura-pirarrã), Amazonas, Brazil

- Nukak (Nukak-Makú), eastern Colombia

- Ocaina, Loreto Region, Peru

- Omagua (Cambeba, Kambeba, Umana), Amazonas, Brazil

- Orejón (Orejon), Napo Province, Ecuador

- Panoan, western Brazil, Bolivia, Peru

- Sharpas

- Siona (Sioni), Amazonas Department, Colombia

- Siriano, Brazil, Colombia

- Siusi, Amazonas, Brazil

- Tariano (Tariana), Amazonas, Brazil

- Tsohom Djapá

- Tukano (Tucano), Brazil, Colombia

- Waikino (Vaikino), Amazonas, Brazil

- Waimiri-Atroari (Kinja, Uaimiri-Atroari), Amazonas and Roraima, Brazil

- Wanano (Unana, Vanana), Amazonas, Brazil

- Witoto

- Murui Witoto, Loreto Region, Peru

- Yagua (Yahua), Loreta Region, Peru

- Yaminahua (Jaminawa, Yamanawa, Yaminawá), Pando Department, Bolivia[69]

- Yora

- Záparo (Zaparo), Pastaza Province, Ecuador

- Zuruahã (Suruahá, Suruwaha), Amazonas, Brazil

Eastern Amazon

editThis region includes Amazonas, Maranhão, and parts of Pará States in Brazil.

- Amanayé (Ararandeura), Brazil

- Araweté (Araueté, Bïde), Pará, Brazil

- Awá (Guajá), Brazil

- Ch'unchu, Peru

- Ge

- Guajajára (Guajajara), Maranhão, Brazil

- Guaraní, Paraguay

- Ka'apor, Maranhão, Brazil

- Kuruaya, Pará, Brazil

- Marajoara, Precolumbian culture, Pará, Brazil

- Panará, Mato Grosso and Pará, Brazil

- Parakanã (Paracana)

- Suruí do Pará, Pará, Brazil

- Tembé

- Turiwára

- Wayampi

- Zo'é people, Pará, Brazil

Southern Amazon

editThis region includes southern Brazil (Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, parts of Pará, and Rondônia) and Eastern Bolivia (Beni Department).

- Aikanã, Rondônia, Brazil

- Akuntsu, Rondônia, Brazil

- Apiacá (Apiaká), Mato Grosso and Pará, Brazil[70]

- Assuriní do Toncantins (Tocantins)

- Aweti (Aueto), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Bakairí (Bakairi)

- Chácobo (Chacobo), northwest Beni Department, Bolivia[69]

- Chiquitano (Chiquito, Tarapecosi), Brazil and Santa Cruz, Bolivia[69]

- Cinta Larga, Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Enawene Nawe, Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Gavião of Rondônia

- Guarayu (Guarayo), Bolivia[69]

- Ikpeng (Xicao), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Itene, Beni Department, Bolivia[69]

- Irántxe (Iranche)

- Juma (Kagwahiva), Rondônia, Brazil

- Jurúna (Yaruna, Juruna, Yudjá), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Kaiabi (Caiabi, Cajabi, Kajabi, Kayabi), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Kalapálo (Kalapalo), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Kamayurá (Camayura), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Kanoê (Kapixaná), Rondônia, Brazil

- Karipuná (Caripuna)

- Karitiâna (Caritiana), Brazil

- Kayapo, Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Kuikuro, Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Matipu, Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Mehináku (Mehinacu, Mehinako), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Moxo (Mojo), Bolivia

- Nahukuá (Nahuqua), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Nambikuára (Nambicuara, Nambikwara), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Pacahuara (Pacaguara, Pacawara), northwest Beni Department, Bolivia[69]

- Pacajá (Pacaja)

- Panará, Mato Grosso and Pará, Brazil

- Parecís (Paressi)

- Rikbaktsa (Erikbaksa), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Rio Pardo people, Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Sateré-Mawé (Maue), Brazil

- Suyá (Kisedje), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Tacana (Takana), Beni and Madre de Dios Rivers, Bolivia[69]

- Tapajó (Tapajo)

- Tenharim

- Trumai, Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Tsimané (Chimané, Mosetén, Pano), Beni Department, Bolivia[69]

- Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, Rondônia, Brazil

- Wari' (Pacanawa, Waricaca'), Rondônia, Brazil

- Wauja (Waurá, Waura), Mato Grosso, Brazil

- Wuy jugu (Mundurucu, Munduruku)

- Yawalapiti (Iaualapiti), Mato Grosso, Brazil

Southwestern Amazon

editThis region includes the Cuzco, Huánuco Junín, Loreto, Madre de Dios, and Ucayali Regions of eastern Peru, parts of Acre, Amazonas, and Rondônia, Brazil, and parts of the La Paz and Beni Departments of Bolivia.

- Aguano (Santacrucino, Uguano), Peru

- Amahuaca, Brazil, Peru

- Apurinã (Popũkare), Amazonas and Acre

- Asháninka (Campa, Chuncha), Acre, Brazil and Junín, Pasco, Huánuco, and Ucayali, Peru

- Banawá (Jafí, Kitiya), Amazonas, Brazil

- Cashibo (Carapache), Huánuco Region, Peru

- Conibo (Shipibo-Conibo), Peru and Amazonas, Brazil

- Ese Ejja (Chama), Beni Department, Bolivia[69]

- Harakmbut, Madre de Dios, Peru

- Amarakaeri, Madre de Dios Region, Peru

- Kareneri, Madre de Dios Region, Peru

- Huachipaeri, Madre de Dios Region, Peru

- Amarakaeri, Madre de Dios Region, Peru

- Hi-Merimã, Himarimã, Amazonas, Brazil

- Jamamadi, Acre and Amazonas, Brazil

- Kaxinawá (Cashinahua, Huni Kuin), Peru and Acre, Brazil

- Kulina (Culina), Peru

- Kwaza (Coaiá, Koaiá), Rondônia, Brazil

- Latundê, Rondônia, Brazil

- Machinere, Bolivia[69] and Peru

- Mashco-Piro, Peru

- Matís (Matis), Brazil

- Matsés (Mayoruna, Maxuruna), Brazil, Peru

- Parintintin (Kagwahiva’nga), Brazil

- Shipibo, Loreto Region, Peru

- Sirionó (Chori, Miá), Beni and Santa Cruz Departments, Bolivia

- Ticuna (Tucuna), Brazil, Colombia, Peru

- Toromono (Toromona), La Paz Department, Bolivia[69]

- Yanesha' (Amuesha), Cusco Region, Peru

- Yawanawa (Jaminawá, Marinawá, Xixinawá), Acre, Brazil; Madre de Dios, Peru; and Bolivia

- Yine (Contaquiro, Simiranch, Simirinche), Cuzco Region, Peru

- Yuqui (Bia, Yuki), Cochabamba Department, Bolivia[69]

- Yuracaré (Yura), Beni and Cochabamba Departments, Bolivia[69]

Gran Chaco

edit

- Abipón, Argentina, historic group

- Angaite (Angate), northwestern Paraguay

- Ayoreo[72] (Ayoré, Moro, Morotoco, Pyeta, Yovia,[69] Zamuco), Bolivia and Paraguay

- Chamacoco (Zamuko),[72] Paraguay

- Chané, Argentina and Bolivia

- Chiquitano (Chiquito, Tarapecosi), eastern Bolivia

- Chorote (Choroti,[72] Iyo'wujwa,[69] Iyojwa'ja Chorote, Manjuy), Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay

- Guana[72] (Kaskihá), Paraguay

- Guaraní,[72] Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay

- Bolivian Guaraní[69]

- Chiriguano, Bolivia

- Guarayo (East Bolivian Guaraní)

- Chiripá (Tsiripá, Ava), Bolivia

- Pai Tavytera (Pai, Montese, Ava), Bolivia

- Tapieté (Guaraní Ñandéva, Yanaigua),[72] eastern Bolivia[69]

- Yuqui (Bia), Bolivia

- Bolivian Guaraní[69]

- Guaycuru peoples, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay

- Kaiwá,[72] Argentina and Brazil

- Lengua people (Enxet),[72] Paraguay

- North Lengua (Eenthlit, Enlhet, Maskoy), Paraguay

- South Lengua, Paraguay

- Lulé (Pelé, Tonocoté), Argentina

- Maká[72] (Towolhi), Paraguay

- Nivaclé (Ashlushlay,[72] Chulupí, Chulupe, Guentusé), Argentina and Paraguay

- Sanapaná[72] (Quiativis), Paraguay

- Vilela, Argentina

- Wichí (Mataco),[72] Argentina and Tarija Department, Bolivia[69]

Southern Cone

edit

- Aché, southeastern Paraguay

- Chaná (extinct), formerly Uruguay

- Chandule (Chandri)

- Charrúa, southern Brazil and Uruguay

- Comechingon (Henia-Camiare), Argentina

- Haush (Manek'enk, Mánekenk, Aush), Tierra del Fuego

- Het (Querandí) (extinct), formerly Argentinian Pampas

- Huarpe (Warpes), Argentina, Chile

- Mapuche (Araucanian), southwestern Argentina and Chile

- Mbeguá (extinct), formerly Paraná River, Argentina

- Minuane (extinct), formerly Uruguay

- Puelche (Guennaken, Pamba) (extinct), Argentinian and Chilean Andes[73]

- Tehuelche, Patagonia

- Teushen (Tehues), extinct, formerly Tierra del Fuego

- Selk'nam (Ona), Tierra del Fuego

- Yaro (Jaro)

Fjords and channels of Patagonia

editLanguages

editIndigenous languages of the Americas (or Amerindian Languages) are spoken by Indigenous peoples from the southern tip of South America to Alaska and Greenland, encompassing the land masses which constitute the Americas. These Indigenous languages consist of dozens of distinct language families as well as many language isolates and unclassified languages. Many proposals to group these into higher-level families have been made. According to UNESCO, most of the Indigenous American languages in North America are critically endangered and many of them are already extinct.[74]

Genetic classification

editThe haplogroup most commonly associated with Indigenous Americans is Haplogroup Q1a3a (Y-DNA).[75] Y-DNA, like (mtDNA), differs from other nuclear chromosomes in that the majority of the Y chromosome is unique and does not recombine during meiosis. This has the effect that the historical pattern of mutations can more easily be studied.[76] The pattern indicates Indigenous peoples of the Americas experienced two very distinctive genetic episodes; first with the initial-peopling of the Americas, and secondly with European colonization of the Americas.[77][78] The former is the determinant factor for the number of gene lineages and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous American populations.[77]

Human settlement of the Americas occurred in stages from the Bering sea coast line, with an initial 20,000-year layover on Beringia for the founding population.[79][80] The micro-satellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Amerindian populations have been isolated since the initial colonization of the region.[81] The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous Alaskan populations exhibit haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) mutations, however are distinct from other Indigenous Americans with various mtDNA mutations.[82][83][84] This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later populations.[85]

See also

edit- Classification of the Indigenous languages of the Americas

- Tribe (Native American)

- Indigenous languages of the Americas

- List of pre-Columbian cultures

- List of traditional territories of the Indigenous peoples of North America

- Population history of Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Smithsonian Handbook of South American Indians

Notes

editReferences

edit- D'Azevedo, Warren L., volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 11: Great Basin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1986. ISBN 978-0-16-004581-3.

- Hann, John H. "The Mayaca and Jororo and Missions to Them", in McEwan, Bonnie G. ed. The Spanish Missions of "La Florida". Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. 1993. ISBN 0-8130-1232-5.

- Hann, John H. A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida, 1996. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513–1763. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8.

- Heizer, Robert F., volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 8: California. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978. ISBN 978-0-16-004574-5.

- Milanich, Jerald (1999). The Timucua. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-21864-5. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Steward, Julian H., editor. Handbook of South American Indians, Volume 4: The Circum-Caribbean Tribes. Smithsonian Institution, 1948.

- Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Bruce G. Trigger, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast. Volume 15. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978. ASIN B000NOYRRA.

- Sturtevant, William C., general editor and Raymond D. Fogelson, volume editor. Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.