Self-managed social centers are community spaces which often feature music venues, infoshops, bicycle workshops and free schools. In French, they are termed espace autogéré and in Italian Centro Sociale Autogestito (CSA), or Centro Sociale Occupato Autogestito (CSOA) if squatted.[1][2] These projects are concrete examples of Temporary Autonomous Zones.[3]

Centers

edit| Name | Image | City | State | Duration | Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 in 12 Club |  | Bradford | England | 1988– | Ongoing | [4] |

| 121 Centre | London | England | 1980s–1999 | Former | [5] | |

| 491 Gallery |  | London | England | 2001–2013 | Former | [6] |

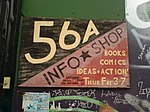

| 56a Infoshop |  | London | England | 1991– | Ongoing | [7] |

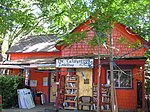

| ABC No Rio |  | New York City | United States | 1980– | Ongoing | [8] |

| ACU |  | Utrecht | Netherlands | 1976– | Ongoing | [9] |

| ADM |  | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 1997–2019 | Former | [10] |

| Albert Street Autonomous Zone |  | Winnipeg | Canada | 1995– | Ongoing | [11] |

| ASCII |  | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 1999–2006 | Former | [12] |

| Au | Frankfurt | Germany | 1983– | Ongoing | [13] | |

| Autonomous Centre of Edinburgh | Edinburgh | Scotland | 1997– | Ongoing | [4] | |

| Bank of Ideas |  | London | England | 2011–2012 | Former | [14] |

| BASE | Bristol | England | 1995– | Ongoing | [15] | |

| BIT | London | England | 1968–1979 | Former | [16] | |

| Binz |  | Zürich | Switzerland | 2006–2013 | Former | [17] |

| Blauwe Aanslag |  | The Hague | Netherlands | 1980–2003 | Former | [18] |

| Blitz |  | Oslo | Norway | 1982– | Ongoing | [19] |

| Bloomsbury Social Centre |  | London | England | 2011–2011 | Former | [20] |

| Bluestockings |  | New York City | United States | 1999– | Ongoing | [21] |

| Boxcar Books |  | Bloomington | United States | 2001–2017 | Former | [22] |

| Brian MacKenzie Infoshop | Washington D.C. | United States | 2003–2008 | Former | [23] | |

| The Brick House |  | Louisville | United States | 1999–2008 | Former | [24] |

| Buridda |  | Genoa | Italy | 2003–2014, 2014– | Ongoing | [25] |

| Camas Bookstore and Infoshop |  | Victoria | Canada | 2007– | Ongoing | [26] |

| Can Masdeu |  | Barcelona | Catalonia | 2001– | Ongoing | [27] |

| Can Vies |  | Barcelona | Catalonia | 1997– | Ongoing | [28] |

| Cascina Torchiera |  | Milan | Italy | 1992– | Ongoing | [29] |

| Catalyst Infoshop |  | Prescott | United States | 2004–2010 | Former | [30] |

| Centre International de Recherches sur l'Anarchisme |  | Lausanne | Switzerland | 1957– | Ongoing | [31] |

| Centro 73 | Chişinău | Moldova | 2010–2010 | Former | [32] | |

| Centro Iberico | London | England | c. 1970s–1982 | Former | [33] | |

| Chanti Ollin |  | Mexico City | Mexico | 2003–2017 | Former | [34] |

| Ché Café |  | San Diego | United States | 1980– | Ongoing | [35] |

| Civic Media Center |  | Gainsville | United States | 1992– | Ongoing | [36] |

| Coffee Strong | Lakewood | United States | 2008–2012 | Former | [37] | |

| Common Ground Collective |  | New Orleans | United States | 2005– | Ongoing | [38] |

| Conne Island |  | Leipzig | Germany | 1991– | Ongoing | [39] |

| Cowley Club |  | Brighton | England | 2002– | Ongoing | [40] |

| Cox 18 |  | Milan | Italy | 1976– | Ongoing | [41] |

| CSOA Forte Prenestino |  | Rome | Italy | 1986– | Ongoing | [42] |

| C-Squat |  | New York | United States | 1989– | Ongoing | [43] |

| DIY Space for London |  | London | England | 2015–2020 | Closed | [44][45] |

| EKH |  | Vienna | Austria | 1990– | Ongoing | [46] |

| Eskalera Karakola |  | Madrid | Spain | 1996– | Ongoing | [47] |

| Extrapool | Nijmegen | Netherlands | 1991– | Ongoing | [48] | |

| Firestorm Books & Coffee | Asheville | United States | 2008– | Ongoing | [49] | |

| Forest Café |  | Edinburgh | Scotland | 2000–2022 | Former | [50][51] |

| Fort Thunder |  | Providence | United States | 1995–2001 | Former | [52] |

| Freedom Press |  | London | England | 1886– | Ongoing | [53] |

| Freedom Shop | Wellington | New Zealand | 1995– | Ongoing | [54] | |

| Grote Broek |  | Nijmegen | Netherlands | 1984– | Ongoing | [55] |

| Hausmania |  | Oslo | Norway | 2000– | Ongoing | [56] |

| Hirvitalo |  | Tampere | Finland | 2006– | Ongoing | [57] |

| Ingobernable |  | Madrid | Spain | 2017–2019, 2020–2020 | Former | [58] |

| Internationalist Books |  | Carrboro | United States | 1981–2016 | Former | [59] |

| Iron Rail Book Collective |  | New Orleans | United States | 2003–2012 | Former | [60] |

| Jura Books |  | Sydney | Australia | 1977– | Ongoing | [61] |

| Kafé 44 |  | Stockholm | Sweden | 1976– | Ongoing | [62] |

| Kasa de la Muntanya |  | Barcelona | Catalonia | 1989– | Ongoing | [28] |

| Klinika |  | Prague | Czech Republic | 2014–2019 | Former | [63] |

| Køpi |  | Berlin | Germany | 1990– | Ongoing | [64] |

| Kulturzentrum Bremgarten |  | Bremgarten | Switzerland | 1990– | Ongoing | [65] |

| Kulturzentrum Reitschule |  | Bern | Switzerland | 1980s– | Ongoing | [66] |

| Kukutza |  | Bilbao | Basque Country | 1996–1996, 1998–1998, 1998–2011 | Former | [67] |

| Ladronka |  | Prague | Czech Republic | 1993–2000 | Former | [63] |

| Landbouwbelang |  | Maastricht | Netherlands | 2002– | Ongoing | [68] |

| Leoncavallo |  | Milan | Italy | 1975– | Ongoing | [69] |

| Lepakko |  | Helsinki | Finland | 1979-1999 | Evicted | [70] |

| London Action Resource Centre | London | England | 1999- | Ongoing | [71] | |

| London Queer Social Centre |  | London | England | 2012–2014 (four locations) | Evicted | [72] |

| Lucy Parsons Center |  | Boston | United States | 1992– | Ongoing | [73] |

| Metelkova |  | Ljubljana | Slovenia | 1993– | Ongoing | [74] |

| Milada |  | Prague | Czech Republic | 1997–2009 | Former | [63] |

| Noisebridge |  | San Francisco | United States | 2007– | Ongoing | [75] |

| OCCII |  | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 1984– | Ongoing | [55] |

| Okupa Che | Mexico City | Mexico | 2000– | Ongoing | [34] | |

| OT301 |  | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 1999– | Ongoing | [55] |

| Patio Maravillas |  | Madrid | Spain | 2007–2010, 2010–2015, 2015–2015 | Former | [76] |

| Poortgebouw |  | Rotterdam | Netherlands | 1980– | Ongoing | [77] |

| Qilombo |  | West Oakland, California | United States | 2011–2019 | Former | [78] |

| rampART | London | England | 2004–2009 | Former | [79] | |

| Really Free School |  | London | England | 2011 | Former | [80] |

| Red and Black Cafe |  | Portland | United States | 2000–2015 | Former | [81] |

| Red Emma's |  | Baltimore | United States | 2004– | Ongoing | [82] |

| RHINO |  | Geneva | Switzerland | 1988–2007 | Former | [83] |

| Rog |  | Ljubljana | Slovenia | 2006–2021 | Former | [84] |

| Rote Flora |  | Hamburg | Germany | 1989– | Ongoing | [85] |

| Rozbrat |  | Poznań | Poland | 1994– | Ongoing | [86] |

| Salon Mazal | Tel Aviv | Israel | 2000s | Former | [87] | |

| Seomra Spraoi |  | Dublin | Ireland | 2004–2015 | Former | [88] |

| Spartacus Books |  | Vancouver | Canada | 1973– | Ongoing | [89] |

| Spike Surplus Scheme | London | England | 1999–2009 | Former | [90] | |

| St Agnes Place |  | London | England | 1969–2005 | Former | [91] |

| Sumac Centre |  | Nottingham | England | 1984– | Ongoing | [92] |

| Syndikalistiskt Forum | Gothenburg | Sweden | 1980– | Ongoing | [93] | |

| Tabacalera de Lavapiés |  | Madrid | Spain | 2010– | Ongoing | [94] |

| Trotz Allem |  | Witten | Germany | 1999–2005, 2006–2006, 2010– | Ongoing | [95] |

| Turun Kirjakahvila |  | Turku | Finland | 1981– | Ongoing | [96] |

| Ubica |  | Utrecht | Netherlands | 1992–2013 | Former | [97] |

| UFFA | Trondheim | Norway | 1981– | Ongoing | [98] | |

| Ungdomshuset |  | Copenhagen | Denmark | 1982–2007, 2008– | Ongoing | [99] |

| Valreep | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 2011–2014 | Former | [100] | |

| Villa Amalia |  | Athens | Greece | 1990–2012 | Former | [101] |

| Vloek |  | The Hague | Netherlands | 2002–2015 | Former | [102] |

| Vrankrijk |  | Amsterdam | Netherlands | 1982– | Ongoing | [103] |

| Vrijplaats Koppenhinksteeg |  | Leiden | Netherlands | 1968–2010 | Former | [104] |

| Wapping Autonomy Centre | London | England | 1981–1982 | Former | [105] | |

| Warzone Centre | Belfast | Northern Ireland | 1986–2003, 2011-2018 | Former | [106] |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Desponds, Didier; Auclair, Elizabeth (2016). La ville conflictuelle: Oppositions – tensions – négociations : [colloque, Cergy, 19–20 novembre 2014]. Éditions le Manuscrit. ISBN 978-2-304-04558-1.

- ^ Webb, Maureen (March 10, 2020). Coding democracy: How hackers are disrupting power, surveillance, and authoritarianism. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-262-04355-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Shaw, Debra Benita (October 24, 2017). Posthuman Urbanism: Mapping Bodies in Contemporary City Space. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-78348-081-4. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Lacey, Anita (August 2005). "Networked Communities: Social Centers and Activist Spaces in Contemporary Britain". Space and Culture. 8 (3): 286–301. Bibcode:2005SpCul...8..286L. doi:10.1177/1206331205277350. S2CID 145336405.

- ^ "Morris, Olive Elaine (1952–1979)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/100963. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "491 Gallery". web.archive.org. December 6, 2019. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ Pell, Susan (2020), "Documenting the fight for the city: The impact of activist archives on anti-gentrification campaigns", Archives, Recordkeeping, and Social Justice, Routledge, doi:10.4324/9781315567846-9, ISBN 978-1-315-56784-6, S2CID 219402555, archived from the original on October 8, 2021, retrieved October 8, 2021

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (July 4, 2006). "For $1, a Collective Mixing Art and Radical Politics Turns Itself Into Its Own Landlord (Published 2006)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Poldervaart, Saskia (2006), "The connection between the squatter, queer and alterglobalization movement. The many diversities of multiculturalism", in Chateauvert, M (ed.), New Social Movements and Sexuality, Sofia: Bilitis Resource Center

- ^ Derks, Sanne (January 19, 2019). "Squatters in Amsterdam lose free haven". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ French, Michelle (September 12, 2001). "Mondragon at five". web.archive.org. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "ASCII in Javastraat is no more — Ascii". web.archive.org. May 31, 2008. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ Weiss, Theresa (August 4, 2017). "Autonomes Zentrum "Au": "Brennpunkt des Linksextremismus"". Frankfurter Allgemeine (in German). Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Walker, Peter; Davies, Lizzy (January 30, 2012). "Occupy London: Evicted protesters criticise bailiffs' 'heavy-handed' tactics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Firth, Rhiannon (March 12, 2012). Utopian Politics: Citizenship and Practice. Routledge. pp. 58–61. ISBN 978-1-136-58072-7. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Crowther, Ashley (December 24, 2020). "Before Lonely Planet - BIT Guides Ruled". AshleyCrowther. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ Feusi, Alois (May 31, 2013). "Die Binz-Besetzer sind abgezogen". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Hoogland, Joyce (December 29, 2018). "Fotoserie: Feestjes en ontruiming van kraakpand de Blauwe Aanslag". Indebuurt Den Haag (in Dutch). Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Monsen, Øistein Norum; Klungveit, Harald S.; Loftstad, Ralf (April 27, 2007). "Politiet stormet Blitz-huset". Dagbladet (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Finchett-Maddock, Lucy (October 12, 2017). Protest, property and the commons : performances of law and resistance. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 9781138570450.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Puglise, Nicole (December 29, 2014). "Bluestockings: The Lower East Side's Last Radical Bookstore". Observer. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "Closing Statement". Boxcar Books. December 2, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ Lowman, Stephen (December 8, 2008). "Anarchist Hangout Surrendering to Market Forces". The Washington Post. pp. B06. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

- ^ "The Brycc House - Louisville Punk/Hardcore History". history.louisvillehardcore.com. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ Biordi, Cristina (June 17, 2016). "Opiemme cambia il volto del Lsoa Buridda di Genova". AGR Press. Archived from the original on April 27, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2021.

- ^ "Police Raid Camas Educational Bookstore | Vancouver Media Co-op". web.archive.org. August 4, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ White, Cristina Tomàs (July 18, 2023). "How an Abandoned Leper Colony Became an Environmentalist's Haven". Bluedot Living. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Debelle, Galvão; Cattaneo, Claudio; González, Robert; Barranco, Oriol; Llobet, Marta (2018). "Squatting Cycles in Barcelona: Identities, Repression and the Controversy of Institutionalisation". The Urban Politics of Squatters' Movements: 51–73. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95314-1_3. ISBN 978-1-349-95313-4.

- ^ Mannu, Giampaolo (2020). "Cascina Torchiera, il Comune di Milano la vuole vendere e la Lega chiede lo sgombero: "Qui cultura e inclusione, è assurdo"". Milano Today. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Rovics, David (August 3, 2007). "Pivotal Moment in the Green Scare". Capitalism Nature Socialism. 18 (3): 8–16. doi:10.1080/10455750701526187. ISSN 1045-5752.

- ^ PRATABUY, Pierre (May 27, 2024). "Musée: au CIRA, tout sur les anars mais point de foutoir". La Libre.be (in French). Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Various (2011). New Urban Topologies: The Chisinau and Minsk experience. Stockholm: Färgfabriken. pp. 80–83. ISBN 978-91-977274-8-8.

- ^ Vague, Tom. "Counter Culture Portobello Psychogeographical History". www.portobellofilmfestival.com. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ a b González, Robert; de Santiago, Diego; Rodríguez, Marco Antonio (2020). "Squatted and Self-Managed Social Centres in Mexico City: Four Case Studies from 1978–2020". Partecipazione e Conflitto. 13 (3): 1269–1289. doi:10.1285/i20356609v13i3p1269.

- ^ Mendoza, Bart. "Cool as Veggie Chili | San Diego Reader". www.sandiegoreader.com. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Dodge, Chris (1998). "Taking Libraries to the Street: Infoshops & Alternative Reading Rooms". American Libraries. 29 (5): 62–64. ISSN 0002-9769.

- ^ "About | Coffee Strong". Archived from the original on May 20, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Ilel, Neille (December 11, 2006). "A Healthy Dose of Anarchy". Reason.com. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Streich, Juliane (September 15, 2011). "20 Jahre "Conne Island": Paradies mit Putzdienst". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Chatterton, Paul (March 2006). ""Give up Activism" and Change the World in Unknown Ways: Or, Learning to Walk with Others on Uncommon Ground". Antipode. 38 (2): 259–281. Bibcode:2006Antip..38..259C. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00579.x.

- ^ Lapolla, Luca (2019). "Social Centres as Radical Social Laboratories". In Gordon, Uri; Kinna, Ruth (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Radical Politics. Routledge. pp. 417–432. doi:10.4324/9781315619880-34. ISBN 9781315619880. S2CID 198064467.

- ^ Mudu, Pierpaolo; Marini, Alessia (March 2018). "Radical Urban Horticulture for Food Autonomy: Beyond the Community Gardens Experience: Radical Urban Horticulture for Food Autonomy". Antipode. 50 (2): 549–573. doi:10.1111/anti.12284.

- ^ "Squatters' Rites". City Limits. September 1, 2002. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Cartledge, Luke (2020). "Out of place – why community venues like DIY Space For London need our help". Loud And Quiet. Archived from the original on June 25, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Goodbye Ormside Street- DIY Space Is Looking For A New Home". diyspaceforlondon.org. June 12, 2020. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Foltin, Robert (2014). "Squatting and Autonomous Action in Vienna 1976–2012". In Katzeff, Ask; van Hoogenhuijze, Leendert; van der Steen, Bart (eds.). The City Is Ours: Squatting and Autonomous Movements in Europe from the 1970s to the Present. PM Press. ISBN 978-1604866834.

- ^ Tseng, Chenta Tsai (July 29, 2020). "¿Cuándo fue la última vez que te aburriste?". El Pais (in Spanish). Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Home". Extrapool. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ "Store Profile: Firestorm Cafe | Revolution by the Book". revolutionbythebook.akpress.org. November 10, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ "2022 update". Tumblr. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Gardner, Lyn (August 7, 2008). "Edinburgh festival: Free for all at the Fringe". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (December 16, 2006). "Looking for Graphic Lightning From Fort Thunder (Published 2006)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 5, 2021.(subscription required)

- ^ Rooum, Donald (Summer 2008). "A short history of Freedom Press" (PDF). Information for Social Change (27). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ Aotearoa Workers Solidarity Movement (November 6, 2014). "Review: Aotearoa Anarchist Review (and Golfing Handbook) |". web.archive.org. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c Various (2009). Witboek kraken. Breda: Papieren Tijger. ISBN 9789067282284.

- ^ "TakingITGlobal - Projects - Hausmania Ecological Pilot Project". web.archive.org. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Alapirtti, Stina (June 24, 2019). "Paljon keskustelua herättänyt Hirvitalo on nykytaiteen keskus keskellä Tampereen Tahmelaa – Kävimme katsomassa mitä talossa tehdään ja millaista siellä on". Aamulehti (in Finnish). Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Moore, Alan W. "Spain Is Making Its Tomorrow". Field (12). Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Grub, Tammy (January 17, 2017). "Bookshop's Franklin Street building is for sale, marking the end". News & Observer.

- ^ "New Orleans: Police shut down Iron Rail Infoshop". Denver Anarchist Black Cross. March 11, 2011. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ "About Us". Jura Books. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Rixer, Victoria (March 17, 2011). "Femårigt frirum firas på 44:an". Fria Tidningen (in Swedish). Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c Trnka, Jan; Novák, Arnošt (2018). "Squatting in Prague". In Squatting Everywhere Kollective (ed.). Fighting for spaces, fighting for our lives: Squatting movements today (1 ed.). Münster: edition assemblage. pp. 151–166. ISBN 9783942885904.

- ^ Karlík, Tomáš (October 31, 2011). "Jak se bydlí ve squatu: jedna noc v legendárním Köpi". National Geographic Česko. Archived from the original on December 24, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "KulturZentrum Bremgarten KuZeB". Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Bänninger, Mirja (2015). Berner Reitschule: Ein soziologischer Blick: Studie auf Anfrage des Gemeinderates der Stadt Bern (Erste Auflage ed.). Basel. ISBN 978-3-906129-91-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Los disturbios por el derribo de Kukutza se trasladan al Ayuntamiento de Bilbao". El País (in Spanish). September 23, 2011. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Janssen, Bert (2013). Cultural freezone Landbouwbelang Maastricht. Maastricht. ISBN 978-90-75924-12-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Membretti, Andrea (July 2007). "Centro Sociale Leoncavallo: Building Citizenship as an Innovative Service". European Urban and Regional Studies. 14 (3): 252–263. doi:10.1177/0969776407077742. S2CID 143887180.

- ^ Hessler, Martina; Zimmermann, Clemens (2008). Creative Urban Milieus: Historical Perspectives on Culture, Economy, and the City. Campus Verlag. p. 303. ISBN 978-3-593-38547-1.

- ^ Sebestyen, Anna (November 19, 2005). "Obituary: Tony Mahoney". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Bettocchi, Milo (2022). "Affect, infrastructure and activism: The House of Brag's London Queer Social Centre in Brixton, South London". Emotion, Space and Society. 42: 100849. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100849. S2CID 245054334.

- ^ "Lucy Parsons Center - An Early History Of The Lucy Parsons Center (short)". lucyparsons.org. March 23, 2019. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Ntounis, Nikos; Kanellopoulou, Evgenia (October 2017). "Normalising jurisdictional heterotopias through place branding: The cases of Christiania and Metelkova". Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 49 (10): 2223–2240. Bibcode:2017EnPlA..49.2223N. doi:10.1177/0308518X17725753. S2CID 149165762.

- ^ Mills, Elinor (October 26, 2012). "Building circuits, code, community at Noisebridge hacker space | InSecurity Complex". CNET News. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Meyer, Luis (June 11, 2015). "Squatter collective Patio Maravillas evicted from unoccupied building". El Pais. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Pomian, Romain (December 9, 2018). "The Short Story – Poortgebouw Rotterdam". Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Tittle, Chris; Dell, Van (April 17, 2017). "Afrikatown Tour and Land Liberation Strategy Session". Sustainable Economies Law Center. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Staff writer (October 19, 2009). "Social centre squatters finally evicted after five year battle". East London Advertiser. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Lyndsey (February 15, 2011). "Really Free School Squat Guy Ritchie's Fitzrovia Pad". Londonist. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019.

- ^ Greif, Jessica (March 25, 2015). "Red and Black Cafe announces closing after 15 years in Portland". Oregon Live | The Oregonian. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Spring 2014, Bret McCabe / Published (March 10, 2014). "The expanding business plans of Red Emma's collective in Baltimore". The Hub. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "ECtHR supports squatters, Rhino v Switzerland, 48848/07" (in French). Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ "Občina nadaljuje rušitvena dela. Odvetnik rogovcev: Za nekatere ljudi ni pravne podlage za izgon". RTV Slovenia (in Slovenian). January 20, 2021. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Jones, Ali (October 2018). "'Militanz' and Moralised Violence: Hamburg's Rote Flora and the 2017 G20 Riot". German Life and Letters. 71 (4): 529–558. doi:10.1111/glal.12212. S2CID 165309877. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ Donaghey, J (2017). "Punk and Anarchist Squats in Poland" (PDF). Trespass. 1: 4-35. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Kloosterman, Karin (August 12, 2005). "The anarchist's playground". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ O’Callaghan, Cian; Lawton, Philip (2015). "Temporary solutions? Vacant space policy and strategies for re-use in Dublin". Irish Geography. 48 (1). hdl:2262/81805.

- ^ "Spartacus Books". CiTR. March 13, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Dee, E.T.C. (January 1, 2016). "Squatted Social Centers in London". Contention. 4 (1). doi:10.3167/cont.2016.040109.

- ^ "London's oldest squat faces end". November 4, 2005. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ "Nottingham Indymedia | Events | Show | Rainbow Centre 25th Anniversary". web.archive.org. May 18, 2015. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ Staff writer (September 28, 2017). "Radikal Bokmässa i Göteborg". Aktuellt Fokus (in Swedish). Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ Moore, Alan W.; Durán, Gloria G. "La Tabacalera of Lavapiés: A Social Experiment or a Work of Art?". Field (2). Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Ernst, Anna (December 11, 2011). "Trotz Allem: Bibliothek als Zeichen für die Gewaltlosigkeit". WAZ. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ "In English". Turun Kirjakahvila (in Finnish). Retrieved May 27, 2024.

- ^ "Tien aanhoudingen bij ontruiming kraakpand Utrecht". NU (in Dutch). May 25, 2013. Archived from the original on March 1, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Fahlenbrach, Kathrin; Sivertsen, Erling; Werenskjold, Rolf (2014). Media and revolt: Strategies and performances from the 1960s to the present. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 368–379. ISBN 978-0-85745-999-2.

- ^ Castle, Stephen (December 18, 2006). "openhagen's calm broken by riots over eviction of squatters". Independent. Archived from the original on May 27, 2007. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Kemman, Alex (2012). "The Valreep: Making the impossible possible". In Hickey, Amber (ed.). A Guidebook of alternative nows. Los Angeles: Journal of Aesthetics & Protest Press. pp. 175–185. ISBN 978-0-615-64972-6.

- ^ Staff writer (September 9, 2016). "Renovated squat Villa Amalia reopens as Athens high school". Ekathimerini. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Mulders, Angelique (September 9, 2015). "Zeven arrestaties bij ontruiming kraakpand De Vloek". Algemeen Dagblad. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Staff writer (November 24, 2005). "Legaal bewonen of niet, krakers blijven". De Volkskrant (in Dutch). Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Leids kraakpand wordt ontruimd". De Volkskrant (in Dutch). February 19, 2010. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2021.(subscription required)

- ^ Berger, George (2006). The story of Crass. London: Omnibus. pp. 191–193. ISBN 978-1846094026.

- ^ Canon, Gabrielle (September 6, 2013). "Warzone Collective: The Alternative Approach to Breaking Down Boundaries in Belfast". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

🔥 Top keywords: Akademia e Shkencave e RPS te ShqiperiseAlexandria Ocasio-CortezBilderberg GroupCristiano RonaldoDong XiaowanMinecraftOperation GladioPrimal cutRiot FestStrictly Come Dancing (series 7)Main PageSpecial:SearchKalki 2898 ADWikipedia:Featured picturesMartin MullICC Men's T20 World CupUEFA Euro 2024.xxxChris MartinA Quiet Place: Day One2024 ICC Men's T20 World CupProject 2025Joe BidenDua LipaCleopatraJamal Musiala2024 NHL entry draftVirat KohliColdplayDeaths in 2024Simone BilesUEFA European ChampionshipCeline DionCricket World CupThe Bear (TV series)Dakota JohnsonZac EfronCyndi LauperKasper Schmeichel2024 Copa AméricaRuben VargasBronny JamesBad Boys: Ride or DieElizabeth IAbu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuseNicole KidmanDonald TrumpRohit SharmaJasprit Bumrah